No one knows exactly when the first mechanical clock was built, but there are several indications that it happened in Europe at the end of the 13th century.

Medieval manuscripts from that time mention a new type of expensive clock, but the word used at the beginning was horologium, the same word that had long been used for other chronometers that had long been used, such as sundials and water clocks. It is therefore impossible to know with certainty what kind of clocks were referred to in these writings.

The Chinese were not the first

As with so many other significant innovations, there are differing opinions as to which part of the world mechanical watches were first made.

Some would argue that the large astronomical clocks built in China in the 11th century should rightfully be considered the first mechanical clocks. But this is a loose interpretation. Admittedly, these were complex devices, but they were always based on the foundation of the water clock, where a body of water was used to measure the passage of time.

At the end of the 13th century, clocks began to be placed in the church towers of Europe.

The clock is 3,500 years old

– 1500 BC

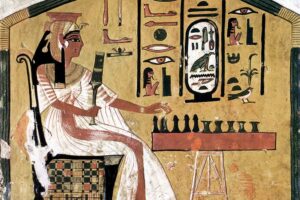

Sundials and water clocks were developed in prehistoric times.

– 13th and 14th century

Mechanical watches appear.

– 16th century

The first pocket watches were made but did not become widespread until the 19th century.

– 17th century

The pendulum clock made timekeeping much more accurate than before.

The mechanical clocks built in Europe certainly also used a so-called detent notch to control how the watch turned.

But what powered the European clocks were weights that went up and down. The clock was thus independent of the cold, in contrast to the water clocks which stopped when the water froze.

British precision paid off

The weights in a mechanical clock powered the movement which in turn turned the timer. And therein lay the big difference – the mechanical clock used the movements of the weights to measure time. This was a huge technological advance.

Measuring time with a reciprocating movement, instead of water or sand, was revolutionary and laid the foundation for all subsequent clocks.

The first clocks known for certain were made by the Englishman Richard of Wallingford in 1336.

He wrote such a detailed description of his clock and its operation that it has been possible to recreate such a clock in modern times. In the latter half of the 14th century, Wallingford’s invention spread throughout Europe.

The church needed precision

The clocks continued to develop in the monasteries of Europe where people had a great need for accurate timing.

Divine services, for example, had to be held at precisely specific times – also sometimes at night, when sundials were completely useless.

Later, clocks were placed in church towers in the middle of cities and towns, and with that they got a bigger role in the eyes of the public. However, the clocks were by no means accurate, and it was probably not until the 16th or 17th century that they began to matter significantly to the general public.

But after the clocks became more accurate, their number rapidly increased and they became a part of people’s daily lives. Businesses began to use clocks to determine working hours – initially in mining and the textile industry.

Gradually, the clocks gained more and more significance in society.

Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) had many irons in the fire. In addition to research on the accuracy of clocks, he also studied Saturn’s rings and acceleration.

The Dutchman who made clocks go right

The first mechanical clocks were not accurate and only measured hours. It wasn’t until the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens invented the pendulum clock that it served the purpose of having a second hand show minutes – and even later the third hand count seconds.

Huygens’ clock was so accurate that it did not err by more than 10 seconds per day. In 1761, a self-taught watchmaker, John Harrison, won a competition run by the British Navy.

The project was to build a clock that showed the correct time, also on board a ship in rough weather. Harrison’s clock did not err by more than a fifth of a second per day, regardless of the weather.

Economic historian Lewis Mumford has identified the clock as the most important explanation for the Industrial Revolution in 18th century England.

The clock made it possible to see time as a commodity that could be bought and sold.

Clocks thus played their part in increasing performance requirements. In an emerging industrial society, people could study how to make the best use of working time. Such research was crucial and the saying “time costs money” was born.

On the other hand, early on, people began to protest the power of the clock over their lives. And after all, maybe it doesn’t have to be so strange that some people still take off their watches on vacation – as if to emphasize that now life should be lived in freedom.

More on the topic:

David S. Landes: Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World, Viking, 2000